Weekly Blog #20

Affordability seems to be the word of the day, especially regarding healthcare and, more specifically, insurance premiums. But as with most widely used economic terms, few people understand what’s actually driving the numbers.

Here’s the uncomfortable math:

- In 2025, total U.S. healthcare spending will reach roughly $5.6 trillion, or 19% of GDP—nearly one-fifth of the entire economy.

- Group healthcare premiums are projected to rise 5% in 2026, the largest increase in 15 years.

- Healthcare costs are forecast to hit $18,000 per person in 2026.

- Over the past 20 years, CPI has increased 56%, while healthcare costs have surged 170%—three times faster.

These numbers are staggering and, candidly, terrifying. You don’t need to be an economist to see the trajectory is unsustainable, particularly for a country with sub-1% population growth, far below the 2.2% replacement rate, and with an aging demographic that consumes exponentially more medical care with each passing year.

The U.S. healthcare system is unique among developed nations. Out of 38 OECD countries, the United States is the only one without universal coverage or a national healthcare system. American healthcare is an intricate blend of private enterprise, insurance carriers, and the federal government—a system with its roots not in medical strategy but in World War II wage and price controls. To compete with capped wages, companies began offering non-wage benefits such as health insurance. After the war, those benefits became entrenched, and corporate America discovered that once you give something, it’s almost impossible to take it back.

In 1950, healthcare consumed just 4% of GDP—a manageable level. Today, at nearly 20%, it’s a macroeconomic crisis. And this raises a critical question: why have sectors like energy and food become dramatically cheaper and more productive over the past decades, while healthcare has moved in the opposite direction?

Energy productivity exploded with innovations such as fracking, horizontal drilling, and advanced seismic mapping. Food production skyrocketed thanks to automation, genetically engineered crops, precision irrigation, and modern logistics. These sectors embraced competition, innovation, and efficiency—healthcare did not. To be clear, this is not a partisan issue. Neither political party has solved it, and both have played a role in creating the system we have today.

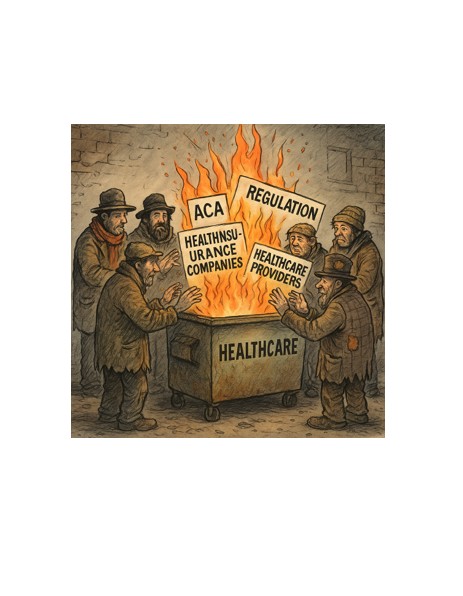

Despite extraordinary scientific and medical discoveries, healthcare productivity—output per unit of input—has barely budged. Unlike sectors subject to free-market competition, healthcare is constrained by layers of regulation, reimbursement mandates, and political incentives that reward complexity and cost inflation—not efficiency. The incentive structure actively discourages innovation, particularly innovations that would lower cost.

The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) was heralded as the long-awaited fix for a broken healthcare system. But instead of realigning incentives, it expanded coverage by dramatically increasing federal subsidies. It’s crucial to understand that the ACA never reduced the actual cost of healthcare. The reason coverage appeared “affordable” for many households is because the federal government stepped in and paid a larger share of the bill. Since 2010, ACA subsidies—premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions—have cost taxpayers roughly $1.2 trillion. When including ACA-related Medicaid expansion, the total exceeds $2 trillion. These subsidies now run more than $110 billion per year and represent a meaningful portion of today’s $2 trillion annual federal deficits. Simply put, affordability improved not because prices fell, but because taxpayers absorbed more of the cost—or more correctly, the national debt increased a commensurate amount.

And the incentives shifted. Insurers no longer operate as risk-bearing entities; instead, they have become administrators of government-funded programs. The moment markets realized the ACA would become the law of the land, healthcare stocks surged as investors priced-in a future driven by subsidies and regulated revenue—not innovation, competition, or cost reduction.

Given this dysfunction, it’s understandable that roughly half the country favors some form of national healthcare. Our current system is expensive, convoluted, and offers no relief in sight. However, national healthcare is not a cure-all. It is rationed care by definition. When the government fixes prices and controls budgets, access is regulated through time rather than through markets.

Let’s compare wait times for hip replacement surgery between the US, Canada and the UK:

- United States: 2–6 weeks (private insurance), 6–12 weeks (Medicare)

- Canada: 25–52 weeks

- United Kingdom: 30–52 weeks

The process is certainly simpler under a single-payer model, but simplicity comes at the cost of speed. Socialized Medicine patients often wait months—or more than a year—for procedures Americans typically receive within weeks. It may be equitable, but it is still rationed.

This contrast underscores the fundamental question: What problem are we trying to solve?

If the goal is universal access, national healthcare achieves that—but with long waits and rationed services. If the goal is innovation, speed, and world-class complex care, the U.S. excels—but at enormous cost.

The tragedy is that our system currently delivers the worst of both worlds: sky-high costs without corresponding efficiency.

The crossroads ahead is unavoidable. Either:

- We deregulate, enabling providers to innovate, automate, and compete in a genuine market, or

- The federal government assumes greater control, and rationing becomes the default.

There is no stable middle ground.

Healthcare in the United States is not merely a policy issue—it is a structural, mathematical, and economic one. Without fundamental incentive reform, costs will continue rising until the system collapses under its own weight.

Mark Lazar, MBA

CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™